Cartoon tradition says that ants are the quickest way to ruin a picnic, but that’s only because there’s no way to make a tick cute (just try it, cartoonists – and if you pull it off, let us see). But ticks aren’t just out to spoil your afternoon in the sunshine (or hike, or camping trip) – they’re voracious, blood-feeding buggers that can carry some nasty diseases. Public health organizations like the Center for Disease Control have been warning us about the dangers of tick-borne illnesses (like the symptoms of Lyme disease) for decades. But recently, with infection rates surging, tick-borne illnesses are putting the public health network – government agencies, university researchers, hospitals, doctors and nurses, nonprofit organizations, and more – into high alert.

Tick Diseases in Humans: Symptoms and Treatments

(Plus Some New Tick Diseases to Keep You Up at Night)

Obviously, the reason the CDC and other public health organizations are worried about ticks, is because of the dangers of tick-borne illnesses. In May 2018, the CDC warned that common tick-borne diseases are on the rise, having tripled in the years between 2004 and 2016. As if that wasn’t enough, researchers have identified nine previously-unknown germs that have either been discovered, or have been newly introduced, in the US. These findings have led to a widespread call across the public health system to educate Americans about common tick-borne diseases: how to prevent infection, recognize symptoms, and find treatment. It’s not an epidemic or pandemic, but it’s a problem to keep an eye on.

The reasons for increase are many, and they’re complicated, but the biggest is global climate change. As overall temperatures increase, the regions where ticks live are expanding, and their active period is getting longer. Travel, development patterns, and habitat change for ticks’ favorite hosts (not just us, but deer, bear, wolves, coyotes, and other animals) are causing the traditional borders of Ticklandia to grow as well. Tick species, and the common tick-borne diseases they carry, are expanding beyond their old territories and overlapping. With many common tick-borne diseases going undiagnosed and unreported, public health education about ticks and the germs they carry is more crucial than ever.

Symptoms of Lyme Disease

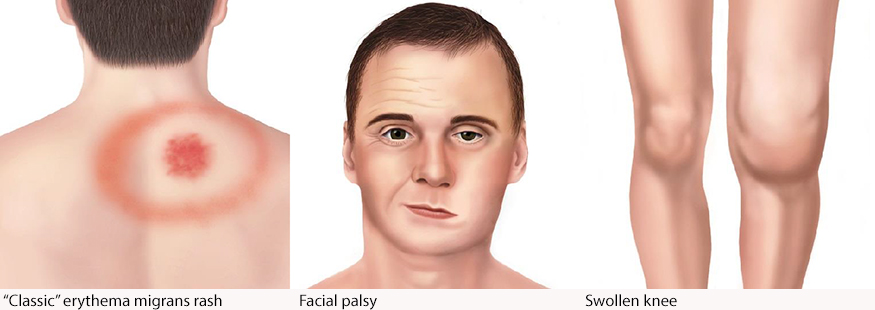

One of most serious tick-borne diseases that the CDC warns about is Lyme disease. Once prevalent primarily in the northeast, Lyme disease has spread across the US along with the spread of the Blacklegged Deer Tick that carries it. When left untreated, Lyme disease can be a debilitating illness, resulting in nerve damage, facial palsy, severe arthritis, heart problems, and even memory loss and dementia.

image source: CDC

With such frightening long-term effects, it’s essential that patients identify symptoms of Lyme disease as soon as possible. The first sign is often the tell-tale “bullseye” rash – a red spot surrounded by a red ring. These may start at the site of the bite, and spread. Flu-like symptoms usually appear within a few days of a bite, including fever, chills, and joint pain. If you’re diagnosed with symptoms of Lyme disease, based on a laboratory test, the first treatment will be an aggressive round of antibiotics; serious infections may even require intravenous antibiotics. But considering the long-term, chronic symptoms of Lyme disease, immediate treatment is essential.

Symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever is another of the most common tick-borne diseases, this one carried primarily by the Dog Tick – also known as the Wood Tick, coming in American and Brown varieties. Like Lyme disease, RMSF is potentially life-threatening, and extremely destructive if left untreated, but can be stopped if caught early. Long-term effects can include damage to the blood vessels, resulting in amputation of extremities, as well as hearing loss and mental deterioration.

Early symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever are similar to those of Lyme disease – flu-like symptoms including fever, headache, nausea, and, of course, the spotted rashes that the disease is named for. Unfortunately, the rash generally comes a few days after the fever, making symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever harder to diagnose than Lyme, where the classic rash appears first. Since it is a bacterial disease, aggressive antibacterial treatment with the drug doxycycline is the most common treatment for symptoms of Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever.

Symptoms of Alpha-Gal Meat Allergy

It’s not the most serious of the common tick-borne diseases, but it may be the strangest. Only identified within the last decade, the alpha-gal meat allergy causes a severe allergic reaction to red meat and dairy products – specifically, the alpha-gal sugar in red meat. One of several relatively new tick diseases, researchers aren’t entirely sure how ticks cause the alpha-gal allergy, but since cows, sheep, and pigs all naturally produce the alpha-gal sugar, their meat triggers the reaction.

It’s not the most serious of the common tick-borne diseases, but it may be the strangest. Only identified within the last decade, the alpha-gal meat allergy causes a severe allergic reaction to red meat and dairy products – specifically, the alpha-gal sugar in red meat. One of several relatively new tick diseases, researchers aren’t entirely sure how ticks cause the alpha-gal allergy, but since cows, sheep, and pigs all naturally produce the alpha-gal sugar, their meat triggers the reaction.

Like most allergies, the alpha-gal allergy causes itchy rashes, nausea, dizziness and headaches, and a severe reaction can even cause anaphylactic shock. There’s some evidence that the allergy can go away on its own, provided sufferers avoid further tick bites, and, obviously, don’t eat beef, lamb, or pork. Lone Star Ticks seem to cause the allergy, and as their territory has spread, so have incidents – more than 5000 since the allergy was discovered.

Symptoms of Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis

Anaplasmosis and Ehrlichiosis are relatively rare tick-borne diseases that are nevertheless increasing in frequency. Public health experts often consider them together, because they have very similar symptoms, usually appearing 1-2 weeks after a bite: flu-like symptoms caused by a bacterial infection, including fever, chills, nausea, headaches, muscle and joint pain, and, rarely, rash. However, they are caused by different bacteria, and carried by different species: Anaplasmosis is generally transmitted by Black-Legged Ticks, while Ehrlichiosis is usually passed by Lone Star Ticks.

If you are experiencing symptoms within two weeks of a tick bite, knowing what kind of tick bit you can be important to diagnosing and treating the infection. Both are treated with doxycycline or related antibiotics, which have been shown to be more effective than other antibiotics.

Symptoms of Powassan Virus

One of the viral infections transmitted by ticks, Powassan Virus is quite rare; only 100 cases have been reported to the CDC in the last 10 years. However, because it is viral, there is very little that can be done by way of treatment, and patients may have to be hospitalized for their protection. Powassan infection attacks the brain and nervous symptom, causing fever, encephalitis (brain swelling), and meningitis. 10% of infections are fatal, and most survivors report permanent neurological damage, including memory loss and headaches. It is primarily carried by Black-Legged Ticks, and is most common in the Northeast and Great Lakes regions.

Know the Enemy: Different Types of Ticks (and What They Do)

Photo by Jared Belson

Let’s get the hard part out of the way for you tick-phobic readers: there are around 900 different species of tick. If that sounds like a lot, consider that there are more than 2000 species of fleas, more than 3500 different species of mosquito, and more than 100,000 species of wasp in the world (including a distinct species of wasp for each of the 800 varieties of fig tree). So as far as nuisance bugs go, there’s a lot less variation in ticks. On the other hand, ticks live just about everywhere, and there are ticks that have adapted to just about any kind of animal – mammals, birds, reptiles, even amphibians (no, not even the frogs and salamanders are safe). So, if you’re somewhere that can sustain animal life, there are ticks that live there too.

For what it’s worth, ticks aren’t bugs – they’re arthropods, specifically arachnids, closely related to spiders. Like spider, ticks have 8 legs, although they hatch with only six; ticks don’t get their seventh and eighth leg until they have their first feeding and molt their skin. Larval ticks can be as small as a poppy seed, as the CDC recently (and vividly) demonstrated in a public service ad that went viral – by freaking people out.

Most ticks have a four-part life cycle, from egg to larva, nymph to adult, and every stage in the life cycle depends on blood. A tick larva needs to find a host as soon as possible, which it does by grabbing onto whatever animal comes close enough. Fortunately, at no stage in life are ticks able to jump, fly, or teleport – they depend on a host literally crashing into them, whereupon they grab on, crawl to a nice, safe spot (preferably where the host can’t scratch or bite them off), and chow down. Some species will hang on to the same host from larva to adult, while others will drop off after feeding to moult in peace. Some even have a different host for each life stage – Lone Star Ticks, for instance, prefer birds as larva, small mammals (like mice) as nymphs, and white-tailed deer as adults.

The good news? Humans are a perfect host at any life stage, since our skin is thin and our blood vessels are close to the surface. Correction: that’s the good news for ticks – not us. Sorry.

When they feed, ticks secrete a chemical compound that makes their bite painless, as well as an anticoagulant – a combination of compounds so unique, researchers are enthusiastically investigating the possible therapeutic uses of tick-derived compounds for fighting blood clots and cardiac diseases. One of the stealthiest bloodsuckers, ticks will never let you know they’re there, which makes a thorough tick check necessary after any trip to the woods.

There are three families of ticks, generally defined by their body type:

Hard-bodied Ticks (Ixodidae) – They haven’t been hanging out at the gym; their bodies are covered in a hard, protective plate. Many of these ticks prefer to bite a host in an inaccessible area and hang on from larva to adulthood, if possible; some may drop off to shed their skin and reattach to another host. Most of the ticks that feed on humans in the US are hard-bodied species.

Soft-Bodied Ticks (Argasidae) – Since Sesame Street taught you how opposites work, you should realize that the primary difference between hard-bodied ticks and soft-bodied ticks is the fact that Argasidae has a soft, leathery shell. There are other differences in their mouths, eyes, and so on, but the obvious is the obvious. Argasidea only make up around 200 of the 900 known tick species, and are less well-studied than the Ixodids.

Nuttalliellidae (The Other One) – There is actually only one species of Nuttalliellidae, and it lives exclusively in southern Africa. They differ enough from both the hard-bodied and soft-bodied ticks to be counted as their own species. Experts consider the Nuttalliellidae to be the current species closest to the ticks’ common ancestor; it looks very similar to fossil records dating back to nearly three hundred million years ago, and they’re so hardy largely because they will feed on just about anything – including us.

Oh, that’s right – fossil records in amber show that ticks were feeding on dinosaurs in the Cretaceous. Next time you’re cursing ticks on your camping trip, remember they were here way before us.

Where Do Ticks Live (Other than My Nightmares)?

The majority of tick species tend to live in the tropics, because hot weather and humidity is the best climate for a tick’s life cycle, but there are three main tick species in the US that affect humans. Where do ticks live in the US? Everywhere; the three main American species used to have fairly defined territories, but in recent years, their boundaries have started to overlap. The most prevalent ticks in the US that feed on people are:

Black-Legged (Deer) Tick

These are the most common tick in the Northeast and Midwest – in fact, they account for around 90% of ticks found in the North. They’re a hard-bodied tick, and they get their name for two obvious features: they have black legs, and they’re most commonly found on deer. That doesn’t mean we’re safe – deer ticks love humans, and they transmit some of the worst tick-borne diseases. The Western Black-Legged Tick is the hipster cousin that moved to the Pacific Northwest and California; nonetheless, it is no cooler than the eastern version, and still dangerous. In some places, they’re called Bear Ticks.

Dog Tick

The Dog Tick is just as creatively named as the deer tick, and has a range that encompasses virtually the entire US. However, in the Midwest and South they are the most common species of tick, much more prevalent than the Black-Legged Deer Tick. American Dog Ticks (also called Wood Ticks) are spread across the US, while Brown Dog Ticks are primarily east of the Rock Mountains; both carry Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, however. The American Dog Tick is fairly colorful, while the Brown Dog Tick is – well, brown. If you pick a tick off your dog, it’s likely a dog tick, since dogs are their preferred host for growing from larva to adult.

Lone Star Tick

Lone Star Ticks are also known as turkey ticks, since the larva and nymph stages favor turkeys for their host, but the adult Lone Star Tick loves a little venison (or at least deer blood). Primarily found in the Southwest and South, as well as Mexico, the name calls to mind Texas. And sure, there are plenty of Lone Star Ticks in Texas, but they’re more likely named for the white dot on their back, which can sometimes look like a star. Ironically, the Texas-themed tick is the one that causes alpha-gal allergy – that severe allergic reaction to red meat we mentioned before.

As for habitat, where to ticks live and thrive? Pretty much anywhere grassy, leafy, or covered in plant debris. As you might guess, that includes virtually all of the United States, save the most arid parts of the desert, and urban areas without any plant growth. Otherwise, it’s fair game for ticks – grasslands, prairie, forests, and anywhere else there are animals to feed on and a ground covering where females can safely lay their eggs.

How to Avoid and Get Rid of Ticks (Is There Any Tick Repellent that Really Works?)

In general, the best way to handle ticks is to not be exposed to ticks. That doesn’t mean you should never leave the house, though; it means taking sensible precautions to avoid common tick-borne diseases whenever you’re hiking or camping in the woods, working in the yard, or letting your pets roam the park.

In general, the best way to handle ticks is to not be exposed to ticks. That doesn’t mean you should never leave the house, though; it means taking sensible precautions to avoid common tick-borne diseases whenever you’re hiking or camping in the woods, working in the yard, or letting your pets roam the park.

- Wear long socks and pants: Ticks usually start at the feet, ankles, and legs, and work their way up. Long socks and pants can hold them back, especially if your pants are tucked into your sock. Look goofy. It’s okay.

- Stay out of high grass and underbrush: These are the areas where ticks tend to lay their eggs, and where tick larvae climb up the grass and lay in wait. No, seriously – they stand at the end of a blade of grass and reach out for the first animal that brushes past.

- Keep to well-beaten paths: Sure, the intrepid hiker wants to wander, but ticks are very unlikely to be on the hard ground of a well-trod path. Where do ticks live? Grass and underbrush – not hard-packed trails.

- Check your pets: You love them, they’re part of the family, but dogs and cats are animals that haven’t the slightest idea about ticks. No matter how hard you try, your dog will dart into the underbrush; your cat will sneak out the back door and stalk through the high grass. And they’ll bring back ticks. Any time your pet is outside, check them thoroughly when they get home.

Tick Repellents

There is no end of tick repellents on the market, from all-natural essential oils to chemical compounds that can be used in sprays, powders, and infused in clothing. Natural compounds include oils and sprays that contain:

- Lemon eucalyptus oil

- Citronella

- Eucalyptus

- Lavender

- Juniper

- Clove

Some believe that apple cider vinegar or vanilla extract can also have a tick-repellent effect. Other natural tick repellent options include diatomaceous earth (it cuts the tick’s shell and dehydrates them). DE can be especially handy in a dog’s fur, or on your hiking socks, but users need to be very careful not to breathe the fine powder. It’s not toxic, but it is damaging to the lungs over time.

As for chemical agents, the best-known tick repellents are DEET and permethrin, as well as picaridin.

- Picaridin is a synthetic version of compounds in black pepper – imagine a little pepper spray that gives ticks the old hot-foot.

- DEET is the most popular, and generally the most effective chemical tick repellent, but it is just that – a repellent; it does not kill ticks.

- Permethrin has become the go-to weapon in the public health crusade against Lyme disease, because it both repels ticks, and kills ticks that come into contact.

Permethrin has been in use since the 1970s, largely by the US military; overuse of permethrin was implicated in Gulf War Syndrome, but VA research found no link. Today, permethrin is in commercial use by the North Carolina-based company Insect Shield, including permethrin-infused, tick-repellent clothing.

Note: Permethrin is believed to be safe for humans and dogs, but cats may be sensitive. Do not expose cats to liquid permethrin; it should be safe after drying.

Keep Your Yard Clean

Female ticks tend to lay their eggs under a safe covering of leaf debris, and the larval ticks, after hatching, will climb the grass or brush to get high enough to grab onto the legs of a passing animal. That means your yard can be a perfect habitat – ticks lay eggs in your mulch, and find shelter in any patches of tall grass. That means the primary ways to keep ticks out of your environment is to make your environment less hospitable:

- Keep grass trimmed short

- Cut out any underbrush if you have woods or natural areas near your house

- Clean up leaf debris

- Use mulch that discourages ticks from laying their eggs (like cedar chips)

Fine, Feathered, Tick-Eating Friends

Many different kinds of birds eat ticks, but one in particular is a tick-eating machine: the Guinea fowl. In recent years, since a yard full of chickens became a qualified hipster credential, Guinea hens have become more popular as well – after all, they’re exotic and cooler than chickens. Guinea fowl have always been a staple of rural farm life, precisely because they can practically eat their weight in insects every day, but people in the suburbs have recently discovered their particular talent for wiping out ticks. Unfortunately, as many a farmer will tell you (if you take the time to ask), Guinea hens are loud, and they never shut up. They’re also notoriously dumb, easy prey for predators, and have a tendency to panic. Take all that, weigh it against wiping out all the ticks in the vicinity, and make your own choices.

If you’re not into noisy, moronic, semi-domesticated birds, attracting wild birds to your yard can be helpful as well; birdhouses, a bird garden full of bird-attracting plants, and other accommodations can bring tick-eaters to you.

creepy tick whisperer

Get a Tick-Killing Robot

Okay, tick-killing robots aren’t quite available on the market yet, but there are some interesting studies being done to develop tick-hunting robots – or, more accurately, robots that trick ticks into hunting them. It seems that ticks are highly attracted to carbon dioxide – the gas exhaled by animals – and can recognize changes in temperature that mean an animal is nearby; one researcher likens them to the Predator in the Arnold Schwarzenneger sci-fi favorite. By using biomimicry, it may one day be possible to build tick-attracting and -eradicating robots – a tick-catching Roomba for the woods, in other words.

What Do I Do If a Tick Bites Me?

No matter what you do, if you spend much time outdoors during the spring, summer, and fall, you’re likely to get a tick bite at some point. Ticks prefer inaccessible areas where they are less likely to be noticed. Since humans lack fur, that means creases and cavities – armpits, ears, crotches, between toes, and even behind knees. Of course, a truly enterprising (or lucky) tick may make it into your head hair, where it can really hide.

Once ticks bite, they really dig in – literally. A tick’s instinct is to burrow into your skin, sinking its head as deeply into the hole as possible so that it cannot be easily extracted. That’s why it’s very common for the tick’s head to break off while trying to remove an embedded tick, especially when people act rashly.

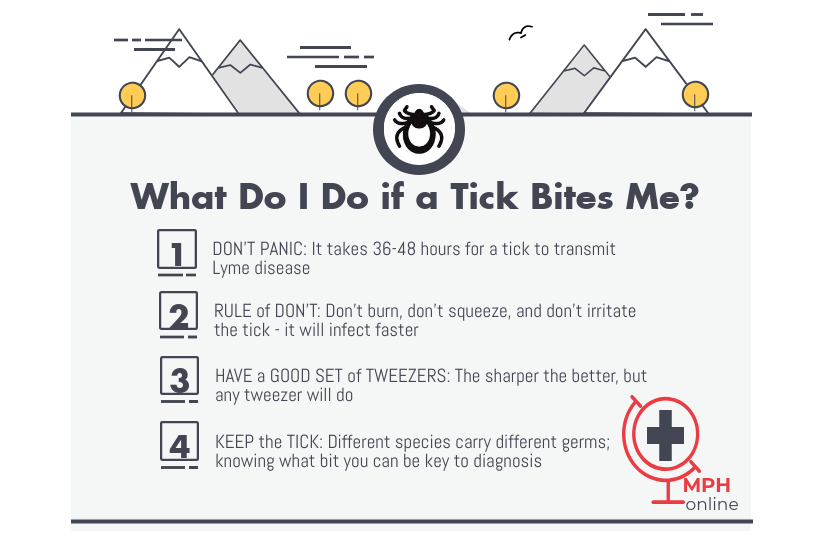

Rule #1: Don’t panic. Yes, they’re gross, yes, they’re creepy, yes, they carry disease, but all in all, it’s still just a tick. If you caught it early – like right after a hike or working in the garden – you have plenty of time. The CDC reports that ticks have to be embedded for at least 36-48 to even transmit Lyme disease, so if you’re still in the 24-hour window, just calm down and focus on getting it out.

Rule #2: The Rule of Don’ts.

- Don’t Burn Them!

- Don’t Squeeze Them!

- Don’t Use Salt! (or acetone, or anything else that will irritate the tick)

All of these methods, no matter what the old wives say, do more harm than good. They cause the tick distress, and – there’s no good way to say this – causes them to vomit their contents back into the wound, along with whatever viruses and bacteria they may be carrying. To keep from inadvertently causing what you’re trying to prevent – exposing yourself to tick-borne illnesses – practice smart tick removal.

Rule #3: Have a good set of tweezers. The sharper the better. There are designated tick tweezers that are specially designed just for removing ticks, head and all, but in a pinch, just about any tweezer will do. The key is to get down to the head, grab tightly, and pull straight out, firmly and decisively. Getting the tick by the head keeps it from throwing its guts up and makes sure the head doesn’t embed.

Rule #4: Keep the tick. If you’re not sure how long you’ve had your little parasite, put the tick in a plastic bag or jar, just in case. That way, you can identify it with certainty, if you start feeling any symptoms. Different ticks carry different diseases, but the initial symptoms of most common tick-borne diseases are pretty similar, so knowing what bit you can help diagnosis. As satisfying as it may be, don’t burn it, stick a needle through it, flush it down the toilet, or anything else vengeful – at least, not until you know what species it is.

Don’t Stay Inside – Just Be Smart!

With all of this admittedly scary information, please, please, please, don’t lock yourself in your home all summer long and wait until the cold weather drives the ticks back into hiding. While you may avoid tick bites (and those common tick-borne diseases), the health benefits of outdoor activity still far outweigh the dangers of ticks. There is a wealth of public health research that shows that exercising outside – even just walking and breathing fresh air – have substantial health benefits.

Fresh air and sunshine have been demonstrated to relieve stress, increase endurance, improve memory and mental functioning, and more. In fact, studies have shown that exercising in the outdoors has significantly greater benefits than exercising indoors, though no one has yet been able to determine quite why. Even just seeing the outdoors has a positive effect; subjects who look at pictures of natural landscapes feel refreshed, and hospital patients who have a view of trees, sky, and water heal faster than those without. The CDC strongly recommends spending time in parks, on trails, and on greenways.

Even though it’s not yet old enough to have a strong body of scientific research, or an organized leadership to set standards, ecotherapy may be the next revolution in mental health and physical wellness. While some unsubstantiated claims of ecotherapy may induce eyerolls in the skeptical (such as the suggestion that touching soil activates mood-enhancing microbes), spending time outdoors is a net positive for nearly everyone – and it would be a shame for the fear of ticks and their nasty germ buddies to keep you indoors all summer.

Instead of hiding, be smart. We’ve only provided the basic outlines of the findings of public health researchers, and there is a strong body of consensus on the ways to prevent common tick-borne diseases and new tick diseases. Follow some sensible, easy advice, stay vigilant, and, by all means, get outside. It’s summer, and a few eight-legged bloodsuckers shouldn’t be allowed to spoil it.

Resources

The CDC’s Thorough (and not at all scary) Tick Guide

EPA Guide to Insect Repellents

The Tick (Spoon!) — This one isn’t about ticks; it’s about The Tick. Ticks aren’t all bad.

Lyme Disease: Prevention, Identification, and Treatment Options — This guide is solid. Check it out!